- Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur Film

- Carl Schmitt Diktatur

- Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur Von

- Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur 2

- Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur Der

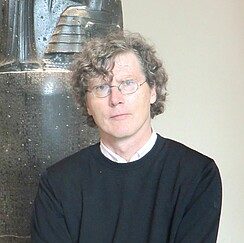

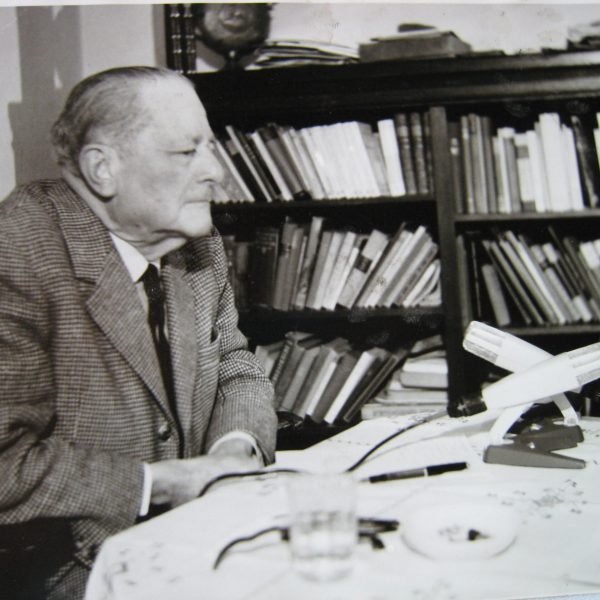

Carl Schmitt (German:; 11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist and political theorist.Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. His work has been a major influence on subsequent political theory, legal theory, continental philosophy and political theolog. His Die Diktatur (1922) distinguished between what he called 'commissarial dictatorship' and 'sovereign dictatorship.' The former, characteristic of the dictators appointed for limited terms during the Roman republic, functioned in times of emergency, not to abrogate, but to preserve the constitutional footing of the nation. Die kommissarische Diktatur und die Staatslehre a) Die staatstechnische und. Carl Schmitt: Die Diktatur. Die Kontroverse um die politische Theologie des Eusebius von Caesarea zwischen Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) und Erik Peterson (1890-1960) Vor dem Hintergrund des mit den Kulturk.

Carl Schmitt was a controversial German catholic intellectual and legal theoretician with ties to the Nazi ideology and party.

Schmitt was born as the son of a businessman in Plettenberg, Westphalia on July 11, 1888; he studied state theory and law in Berlin, Munich and Strassburg and took his graduation and State promotion exams in Strassburg in 1915.

In 1921, Schmitt became a professor at the university of Greifswald, where he published his essay “Die Diktatur” (“On Dictatorship”), in which he discussed the foundations of the newly-established Weimar Republic, emphasising the office of the Reichspräsident. Although most Anglo-American scholars rate “The Concept of the Political” as occupying a central place in Schmitt’s work, this may simply be the result of the historical fact that this work was the first of Schmitt’s essays to be published in English. In many important ways, “On Dictatorship” is equally important, as its central theme presages much of Schmitt’s later work. For Schmitt, a strong dictator could embody the will of the people more effectively than any legislative body, as it can be decisive, whereas parliaments inevitably involve discussion and compromise:

“If the constitution of a state is democratic, then every exceptional negation of democratic principles, every exercise of state power independent of the approval of the majority, can be called dictatorship.”

States must rule, and rule must be exercised decisively. For Schmitt, every government capable of decisive action must include a dictatorial element within its constitution. Thus, in “Die Diktatur,” we find Schmitt's judgement that dictatorships can be more meaningfully democratic than democracies.

This was followed by another essay in 1922, titled “Politische Theologie” (“Political Theology”); in it, Schmitt, who at the time was working as a professor at the University of Bonn, further substantiated his authoritarian theories, effectively denying free will based on a catholic world view. Another year later, Schmitt defended emerging totalitarian power structures in his paper “Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus” (roughly: “The Thought-Historical Situation of Today's Parliamentarianism”).

Schmitt changed universities in 1926, when he became professor for law at the Hochschule für Politik in Berlin, and again in 1932, when he accepted a position in Cologne. It was in Cologne, too, that he wrote another paper, “Der Begriff des Politischen” (“The Concept of the Political”), in which he developed his controversial state law theories. Apart from his academic funtions, Schmitt was counsel for the Reich government in the case “Preussen contra Reich” when the SPD led Prussian government disputed its dismissal by the right-wing von Papen government. One of the counsels for the Prussian government was Hermann Heller. In German history, this sad struggle leading to the de facto destruction of federalism in the Weimar republic is known as the 'Preussenschlag'.

Schmitt's theories in this paper were later used by the Nazis for an ideological foundation of their dictatorship, and Schmitt was later accused of having justified the “Führer” state with regard to legal philosophy. In fact, Schmitt, who became a professor at the University of Berlin in 1933 (a position he held until the end of World War II) joined the NSDAP on May 1, 1933; he quickly was appointed “preußischer Staatsrat” by Hermann Göring and became the president of the “Vereinigung nationalsozialistischer Juristen” (“Union of National-Socialist Jurists”) in November.

Half a year later, in June 1934, Schmitt became editor in chief for the professional newspaper “Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung” (“German jurisprudents' newspaper”); in July 1934, he justified the political murders of the Night of the Long Knives as the “highest form of administrative justice” (“höchste Form administrativer Justiz”).

Schmitt presented himself as a radical anti-semite and also was the chairman of a law teachers' convention in Berlin in October 1936, where he demanded that German law be cleansed from the “Jewish spirit” (“jüdischem Geist”); nevertheless, two months later, in December, the SS publication “Das schwarze Korps” accused Schmitt of being an opportunist and called his anti-semitism a mere mock-up, citing earlier statements in which he criticised the Nazi's racial theories. After this, Schmitt soon lost all of his prominent offices, and retreated from his position as a leading Nazi jurist, although he remained as a professor in Berlin.

Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur Film

In 1945, Schmitt was captured by the American forces; after spending more than a year in an internment camp, he returned to his home town of Plettenberg following his release in 1946. Despite being isolated in the scientific and political community, he continued to study international law from the 1950s on.

Carl Schmitt Diktatur

A state of exception (German: Ausnahmezustand) is a concept introduced in the 1920s by the German philosopher and jurist Carl Schmitt, similar to a state of emergency (martial law) but based in the sovereign's ability to transcend the rule of law in the name of the public good.

Theory[edit]

'In Schmitt's terms,' Masha Gessen wrote in Surviving Autocracy (2020), when an emergency 'shakes up the accepted order of things...the sovereign steps forward and institutes new, extralegal rules.'[1]

This concept is developed in Giorgio Agamben's book State of Exception (2005)[2] and Achille Mbembe's Necropolitics (2019).[3][4] It can be either grounded upon autonomous sources of law (like international treaties) or featured as external to the juridical order.[5]

Historical examples[edit]

The typical example from Nazi Germany is the Reichstag Fire (the arson against German parliament) which led to President von Hindenburg's Reichstag Fire Decree following Hitler's advice. The consequences of entering a state of exception may unroll slowly. 'Even the original Reichstag Fire was not the Reichstag Fire of our imagination—a singular event that changed the course of history once and for all,' Gessen wrote, pointing out that the Second World War did not begin for another six years after the Reichstag burned.[1]

Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur Von

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Carl Schmitt Die Diktatur 2

- ^ abGessen, Masha (2020). 'Chapter 2: Waiting for the Reichstag Fire'. Surviving Autocracy. Riverhead. ISBN9780593188941.

- ^'State of Exception'. uchicago.edu.

- ^'Necropolitics 2003'. Duke University Press.

- ^'Necropolitics 2019'. Duke University Press.

- ^Arthur Percy Sherwood , 'Tracing the American State of Exception from the George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump Presidencies', (2018) 8:1 online: UWO J Leg Stud 1, pp. 2-3.

Sources[edit]

- Carl Schmitt, Die Diktatur. Von den Anfängen des modernen Souveränitätsgedankens bis zum proletarischen Klassenkampf, 1921.

- Carl Schmitt, Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität, 1922.